Ch. 17. Diplomas

Version 4.1 beta (4 June 2025) – cf. version 4.0 beta (23 March 2024)

by Odd Einar Haugen and Nina Stensaker

17.1 Introduction

This chapter deals with the encoding of diplomas, i.e. the large corpus of short, mostly legal documents from ca. 1200 and onwards. The term diploma is commonly used in the Nordic countries for these documents, and it is this term we will use here. Diplomas are often referred to as charters in English and Urkunden in German, but these terms are not regarded as being strictly equivalent. In a Nordic context, the term “diploma” is well understood, and there will hardly be any doubt as to its meaning or the corpus it refers to.

Often only a page long, diplomas are unique in the sense that they almost always are issued with an exact date and location. Compared with the corpus of codices, they contain a high number of names of persons and places. For this reason, diplomas are an important source for onomasts and historians, but also for language historians and linguists in general.

We recommend that in spite of their brevity, each diploma should be encoded as a single and individual document. In general, they are well preserved, although there are examples of fragmented diplomas as well as palimpsests. In size, they are comparable to many fragments of codices, but unlike fragments, diplomas usually carry a complete text. The average length of Norwegian diplomas in the period 1200–1350 is no more than 230 words (Haugen 2018, p. 243).

Please note that this chapter only deals with Norwegian diplomas. At a later stage we hope to include other Nordic diplomas in this chapter.

A general introduction to Norwegian diplomas is found in Hamre 1972, and, more consicely, in Jørgensen 2013, pp. 252–261. It is also worth looking into Agerholt 1929–1932.

The two major sources for the edition and cataloguing of Norwegian diplomas are Diplomatarium Norvegicum (DN) and Regesta Norvegica (RN). The first volume of DN was published in 1847, and it has now reached vol. 23 (published in 2011). In each volume, the diplomas are published in chronological order. The series is ongoing, and vol. 24 (as well as the second fascicle of vol. 20) are now in preparation. RN has been published in a strictly chronological order sine the first volume in 1989, and has reached the year 1430 with vol. 10. Vol. 11 is now in preparation. Note that RN also catalogues lost documents, i.e. documents only known from other sources. Both series are available online:

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum (up to and including vol. 23).

- Regesta Norvegica (up to and including vol. 10).

Of particular interest for Norwegian diplomas up to and including 1310 are two volumes in the series Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi (CCN). They offer updated diplomatic transcriptions of all original diplomas in the Norwegian language from this period, supplied with photographic facsimiles and translations into Modern Norwegian:

- Hødnebø, Finn, ed. 1960. Norske diplomer til og med år 1300. Available online from The National Library (for Norwegian IP addresses).

- Simensen, Erik, ed. 2002. Norske diplom 1301–1310. Not presently available online.

The CCN series is not likely to be continued.

A separate catalogue for diplomas have been set up as part of the Medieval Nordic Text Archive.

Finally, please note that this chapter at times may look rather complex, so it can be helpful to download the two example files in ch. 17.5 below (at least for those who are familiar with reading “raw” XML documents). They will show what the recommendations below mean in practice.

17.2 Originals and copies

The great majority of medieval Nordic diplomas are original texts, preserved in a single version. The encoding of these will be based on the same procedures as other texts in the Menota archive. As mentioned above, they are fairly short, usually no more than a single leaf of parchment. They can be compared to the many editions of codex fragments in the archive, such as those with the signature NRA-norrfragm. The text encoding as such is in principle identical to that of codices.

Some diplomas have been preserved in more than one version (variant diplomas), while yet others are preserved as copies of one or more lost originals (vidimus diplomas). These cases will be discussed in ch. 17.2.2–17.2.5 below.

In this subchapter, we will be relying on a corpus of Norwegian diplomas up to and including 1310. With very few exceptions, these have been published in the series Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi (CCN) by Finn Hødnebø (1960) and Erik Simensen (2002). In these editions, the diplomas total 170, but due to some changes in the categorisation suggested here, a total of 174 diplomas has been reached.

17.2.1 Original diplomas

An original diploma is a document preserved in a single copy, and is thus equivalent to the concept of a codex unicus in the realm of general codicology. While there often will be doubt as to the stemmatic position of a codex unicus, there is less doubt as to a diploma. Unless the diploma explicitly states that it is a copy (which will be discussed in ch. 17.2.3 below), one may assume that it is an original.

While diplomas with very few exceptions are documents of a single page, many of them have some additional, but usually short text on the back. We encode the front page as fol. 1r, and the back page as fol. 1v.

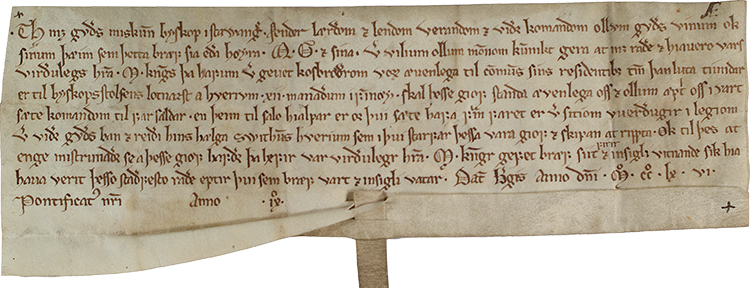

Ill. 17.1. DN 2:13, issued in Bergen in 1266. Note the dating in Roman numerals in the bottom line to the right. We have every reason to believe that this is an original, and that it was issued in the year stated.

The diploma displayed in ill. 17.1 is a well written specimen kept in a formal, non-cursive script. This kind of script was dominant in the Norwegian diplomas up to ca. 1280, but from that point onwards the great majority of diplomas were written in a cursive script. They are not as easily readable, but the amount of unclear readings in the corpus of diplomas remains low compared to e.g. codices and fragment of codices.

As mentioned above, there are several introductory works that one may consult. With respect to the diploma in ill. 17:1, one may benefit from the presentation of it in Jørgensen (2013, 252–261), in Norwegian, or (2020, 156–166), in German.

Some diplomas have text on the seal straps, such as DN 1:89. The diploma text and the text on the seal strap have been encoded in two separate files, but with signatures that clearly reflect the connection between them. In this case, the text of the diploma has been given the signature DN 1:89 text and the text on the seal strap, DN 1:89 sigillum.

17.2.2 Variant diplomas

Variant diplomas are diplomas preserved in more than one version, although usually very close in wording. This is frequently the case for codices, where in many cases a high number of copies have been preserved. It may be the case that one of the diplomas is the exemplar (Norw. ‘forelegg’) of the other diploma(s), but it is also possible that the actual exemplar is lost, so that the preserved diplomas are siblings. The safest solution is to regard them as variant texts on an equal footing, distinguishing between them with an ‘a’ and a ‘b’, etc. In the present corpus, the maximum number of variant diplomas is just two.

Especially in cases where there is little variation between the two documents, one may argue that they will have a larger weight in the corpus than if just one of them had been selected for inclusion (perhaps with variant readings from the other document). We believe that the number of variant diplomas is so low in the whole corpus that it does not skew the data to a particularly high degree. Compared with the whole Menota archive, where for example the Landslǫg text has been published in seven manuscripts (of a total of around 40 manuscripts), the degree of variance in the diploma corpus is negligible.

In the corpus of Norwegian diplomas up to and including 1310, we are only aware of five instances of variant diplomas. We recommend that each variant diploma is encoded and published separately, and for this reason we have added an ‘a’ or ‘b’ to the DN numbers for the purpose of identification:

| DN | RN | Date | Place | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

3:47 a | 3:7 | 1301-05-18 | Nidaros | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘a’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 2) |

3:47 b | 3:7 | 1301-05-18 | Nidaros | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘b’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 2) |

5:44 a | 3:71 | [1303-01 – 1303-03-07] | Ås, Jämtland | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘a’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 13) |

5:44 b | 3:71 | [1303-01 – 1303-03-07] | Ås, Jämtland | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘b’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 13) |

2:68 a | 3:108 | 1303-08-18 | Nidaros | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘a’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 17) |

2:68 b | 3:108 | 1303-08-18 | Nidaros | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘b’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 17) |

2:77 a | 3:225 | 1305-01-26 | Stavanger | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘a’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 33) |

2:77 b | 3:225 | 1305-01-26 | Stavanger | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘b’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 33) |

3:88 a | 3:681 | 1310-04-14 – 1310-10-13 | Nidaros | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘a’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 85) |

3:88 b | 3:681 | 1310-04-14 – 1310-10-13 | Nidaros | Regarded as one document in DN and RN, but copy ‘b’ published separately in CCN (vol. 10, no. 85) |

This analysis is in accordance with the approach by Erik Simensen (2002) in his CCN edition of diplomas 1301–1310.

17.2.3 Vidimus diplomas

A challenging category is the “vidimus diploma”, henceforward a “vidimus”, as it also is called in German (Latin ‘we have seen’). In a Nordic context, the term “vidisse” (Latin ‘having seen’) is often used. A typical vidimus will contain a “frame text” (Norw. ‘rammetekst’), stating that the present diploma is a true copy of an earlier diploma, then the copy itself, usually called a “transcript”, and finally a concluding frame text with the dating of the vidimus. In some cases a vidimus diploma may contain more than one transcript.

From a source critical point of view, one would prefer to extract the transcript and treat it like the earliest source text, and this is what typically has been done in Diplomatarium Norvegicum and Regesta Norvegica. However, in the context of what we might call documentary editing, we suggest that it is the actual vidimus document which is the primary source, and that the transcript should be dated in accordance with the vidimus. In some cases, the temporal distance between the vidimus and the original document is small, perhaps within the same year or even month. In other cases, it is much larger.

Jan Ragnar Hagland (1976) offers an important study of the copying process in the Norwegian vidimus diplomas. He concludes that the transcripts indeed were being done “orð ifra orðe” (‘word by word’), but that they were rendered in the orthography of the vidimus scribe. When there was a considerable lapse in time between the original and the vidimus, the orthographical differences between the two might become substantial.

In the corpus of Norwegian diplomas up to and including 1310, there is one example of a vidimus containing a transcript of a preserved original:

| DN | RN | Date | Place | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

21:8 | 3:544 | 1308-12-01 | [Eidsvoll] | Preserved diploma issued 24 February 1270, probably in Lom (DN 21:1 / RN 2:84) |

These two documents illustrate the copying process clearly. The original document from 1270 (DN 21:1) is a diploma of 220 words. The vidimus of 1308 (DN 21:8) contains the original text as a transcript, and adds a frame text in the initial part of the diploma as well as in the final part. Subsequently, it has become a document of 326 words, of which only the frame text is new.

There are furthermore six examples of vidimus diplomas containing a transcript of a lost original.

| DN | RN | Date | Place | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2:23 | 2:468 | 1286-08 – 1287-05-02 | Oslo | Lost original from 1286-08-28 ca (DN 2:22 / RN2:440); the vidimus in DN 2:22 not finished, “ufuldendt” |

4:52 | 3:34 | 1301-12-13 | Bergen | Lost original from 1301-07-10 (DN 4:51 / RN 3:14) |

5:46 | 3:245 | 1305-05-31 | Tønsberg | Lost original from 1303-01 – 1303-03-07 (DN 5:43 / RN 3:70) |

2:86 | 3:424 | 1307-09-11 | Nidaros | Lost original from 1279-01-01 – 1279-01-07 (DN 2:18 / RN 2:211) |

4:78 | 3:535 | 1308-10-08 | Tuv, Vestre Slidre | Lost original from 1308-06-11 (DN 4:77 / RN 3:491) |

3:81 | 3:596 | 1309-07-20 | Avaldsnes | Lost original from 1309-05-12 (DN 3:81 / RN 3:596) |

There are four examples of vidimus diplomas containing two transcripts. Also in these cases, the originals have been lost:

| DN | RN | Date | Place | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

3:46 | 2:1070 | [1300 ca] | [Nidaros] | Lost originals from 1267-08-16 and 1268-08-10 (DN 3:10 / RN 2:1059 and DN 3:11 / RN 2:1075) |

1:106 | 3:143 | after 1303-12-06 | [Bergen] | Lost originals from 1303-12-06 and after 1303-12-06 (DN 1:97 / RN 3:140 and DN 1:103 / RN 3:141) |

2:79 | 2:666 | 1292-03-02 – 1292-03-08 | Bergen | Lost originals from 1292-03-11 and after 1303-12-06 (DN 2:33 / RN 2:667 and DN 2:33 / RN 3:144) |

4:63 | 3:354 | after 1306-08-05 | [Stavanger] | Lost originals from 1306-05-15 and 1306-08-05 (DN 4:63 / RN 3:330 and DN 4:65 / RN 3:353) |

Finally, there is one example of two vidimus diplomas which are copying a single lost original. In this case, we recommend that both vidimus diplomas should be edited and published.

| DN | RN | Date | Place | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2:48 | 2:979 | 1299-05-16 | [Stavanger?] | Lost original from 1299-04-07 (RN 2:973), this vidimus correctly dated 1299-05-16 (RN 2:979), erronously 1299-04-07 (DN 2:48) |

2:49 | 2:976 | 1299-04-22 | Oslo | Lost original from 1299-04-07 (RN 2:973), this vidimus dated 1299-04-22 (DN 2:48 / RN 2:976) |

In the present corpus, there are no examples of a vidimus diploma where the original has been preserved. According to the abovementioned study by Jan Ragnar Hagland (1976), p. 22, the earliest example of this is an original dated 1325-04-12 (DN 3:141) copied in a vidimus dated 1327-01-05 (DN 3:145).

17.2.4 Chirograph diplomas

A special case is the chirograph. This is a diploma which was written with two identical versions of the text on the same leaf, having the text “Chirographus” or similar across the middle part. Afterwards, it was usually cut in a zig-zag manner, so that one easily could put the two separated pieces together and confirm that they belonged to the same document.

There are a couple of chirographs in the corpus, but neither is preserving both versions of the text. If this had been the case, we suggest that each text should be treated as a variant diploma in accordance with ch. 17.2.2 above.

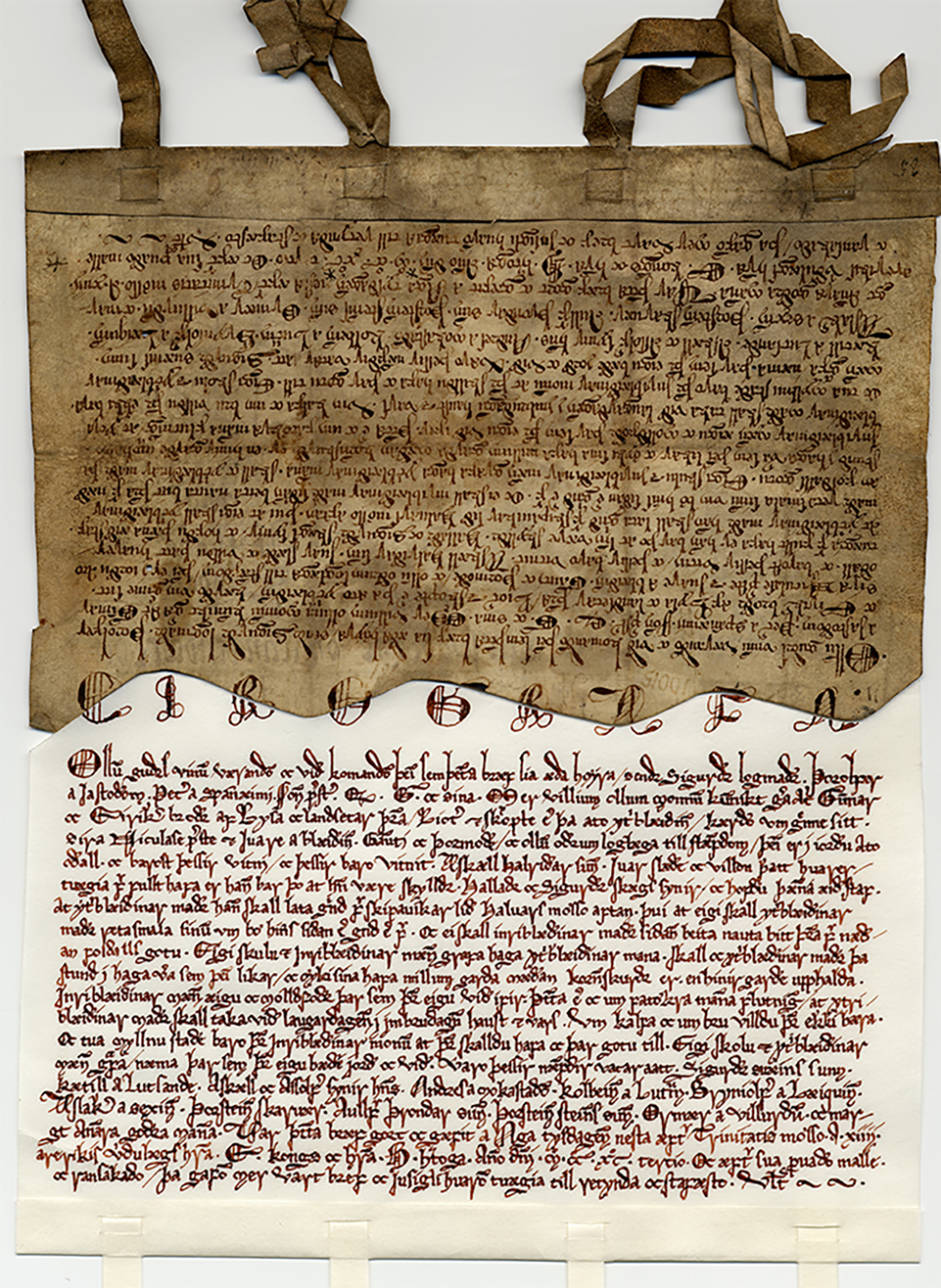

The Aga diploma, DN 4:6, is an outstanding example of a chirograph. In ill. 17.2, it is displayed with a reconstruction of the lost half.

Ill. 17.2. DN 4:6, issued in Aga, 26 May 1293.

The writing on the missing part of the chirograph in DN 4:6 has been reconstructed by the calligrapher Bas Vlam.

17.2.5 Letter books

Letter books (Norw. brevbøker or kopibøker, Lat. registra) containing copies of incoming and outgoing letters were common during the Middle Ages. A few such books are known from medieval Norway, although preserved only fragmentarily. Most well-known is Bergens kopibok, made by the bishops of Bergen during the period 1305–1342 with occasional later entries. The book itself is lost (likely in the Copenhagen fire of 1728), but its contents are known from reliable transcripts. For further details, see KLNM vol. 1, cols. 475–476, vol. 2, cols. 229–233, and Berulfsen 1948, especially pp. 34–46.

The manuscript collector Árni Magnússon had exact copies of a number of diplomas made, so-called apographa, now in the Arnamagnæan Collection. Árni himself wrote on one of these transcripts (DI 6:462, which exists both in original and as an apograph): “accuratisimè ɔ: ordriett, stafriett, bandriett, punctriett” (i.e. faithfully with respect to words, spelling, abbreviations and punctuation). Such transcripts were made of Bergens kopibok, although it is not known whether every document in the book was copied. The apographa are as reliable as copies can be and may – with caution – serve as sources to the language of the original, because they were made out of an antiquarian interest in the original. In this respect, they differ sharply from the medieval practice of copying as seen in the vidimus diplomas, which were rendered “orð ifra orðe” (‘word by word’), but in the orthography of the copyist (cf. ch. 17.2.3 above).

17.3 Header

Due to the huge number of charters and their overall brevity, we recommend a fairly simple header. Below, it has been exemplified with two Norwegian diplomas: one from Aga (DN 4:6, 26 May 1293), which as been encoded from scratch, and another from Bergen (DN 2:93, 6 February 1309), which has been converted from files made during the Documentation project in Oslo and recently updated according to the recommendations in this chapter. We will refer to them as the Aga and the Bergen diploma hereafter.

The diploma header is in most respects identical to the manuscript header discussed in ch. 14 and exemplified in app. E. The present chapter will focus on the header of a typical diploma rather than a manuscript (codex).

17.3.1 Introduction

All diplomas are examples of a single-text source, as exemplified in ch. 14.7 above. The header has four major parts:

| Elements | Contents |

|---|---|

| <fileDesc> | A file description |

| <encodingDesc> | An encoding description |

| <profileDesc> | A text profile |

| <revisionDesc> | A revision history |

This chapter will discuss the recommended amount of information for each of the four parts. The first of these, the file description is the largest of the four, so for practical reasons we will divide it into two subchapters, ch. 17.3.2 covering the title, editor, extent and publication of the diploma, and ch. 17.3.3 covering the contents of the diploma.

17.3.2 The file description: title, edition, extent and publication

The file description is a mandatory part of the header, cf. the TEI P5 Guidelines, ch. 2.2. We begin by discussing the meta-level information on the file history, described in following four elements:

| Elements & attributes | Explanation |

|---|---|

| <titleStmt> | Information on the title, editor and other people who have been responsible for the edition. |

| <editionStmt> | A description of the edition (i.e. version), typically by means of a number and a date. |

| <extent> | The size of the file, preferably specified in the number of words contained in the text. |

| <publicationStmt> | A statement of the publication, i.e. the publisher of the text, reference number, date of publication, and availability. |

The file description contains a number of elements, several of which were discussed in ch. 12 above (<name>, <persName>, <forename>, <surname> and <addName>).

17.3.2.1 Title statement

In the <titleStmt>, the <title> element gives the title of the document. The title is divided into two parts, divided by a colon:

- The volume and text number in Diplomatarium Norvegicum (DN), e.g. DN 4:6 (for volume 4, number 6).

- States that the present text is a digital edition.

<title>DN 4:6 : A digital edition</title>In addition to the title, the <titleStmt> must also list the editor(s) and other contributors to the edition. We recommend that one or more people (or institutions) are identified as the main editor(s) of the text in the <editor> element. In the case of the Aga diploma, which has been transcribed and encoded from scratch, there is a single editor:

<editor>

<name>

<persName>Nina Stensaker</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</editor>Multiple main editors should either be listed either in alphabetical order, if equally responsible, or in order of importance concerning the editing work.

Institutions as well as individuals may be listed as editors. If an institution is regarded as the editor, that should be specified by the attribute @role:

<editor role="institution">

<orgName>Språksamlingane</orgName>

</editor>The institution “Språksamlingane” is now located at the University of Bergen, but was until 2016 part of the University of Oslo. We suggest that the collective work performed at the University of Oslo and now at the University of Bergen is attributed to the institution “Språksamlingane” (or, in English, “The language collections”).

After having stated the editor(s) of the file, one or more <respStmt> elements should specify the main tasks done by each editor. To simplify elicitation of tasks in the catalogue, the type of responsibility is also stated in a @resp attribute. In the case of the Aga diploma, there are three responsibility statements. This is information which in a typical printed edition would be given in the preface, or even on the title page:

<editor>

<name>

<persName>Nina Stensaker</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</editor>

<respStmt resp="annotation">

<resp>Transcription and annotation by</resp>

<name>

<persName>Nina Stensaker</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>

<respStmt resp="programming">

<resp>menotaBlitz.plx program written by</resp>

<name>

<persName>Robert K. Paulsen</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>

<respStmt resp="project overview">

<resp>Project overview</resp>

<name>

<persName>Odd Einar Haugen</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>In the case of a text which has been developed through several stages (possibly at more than one institution), the <editor> and the <respStmt> elements will by necessity be longer. This is the case for the Bergen diploma, which was transcribed by people working at Gammelnorsk ordboksverk in Oslo, converted to XML by The Documentation Project (Dokumentasjonsprosjektet), also in Oslo, and finally converted to full, Menotic XML in Bergen. This can be recorded as follows:

<editor role="institution">

<orgName>Språksamlingane</orgName>

</editor>

<respStmt resp="transcription">

<resp>Transcription</resp>

<name>Many persons employed by Gammelnorsk ordboksverk,

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Oslo</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>

<respStmt resp="digitisation">

<resp>Digitisation and conversion to electronic form</resp>

<name>

<orgName type="affiliation">The Documentation Project</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>

<respStmt resp="file conversion">

<resp>Conversion to Menotic XML</resp>

<name>

<persName>Christian-Emil Smith Ore</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Oslo</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>

<respStmt resp="file conversion">

<resp>Reorganisation and revising of the XML file</resp>

<name>

<persName>Odd Einar Haugen</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>

<respStmt resp="project overview">

<resp>Project overview</resp>

<name>

<persName>Odd Einar Haugen</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName>

</name>

</respStmt>17.3.2.2 Edition statement

The <editionStmt> should be used to specify whether the present text is a new or a revised edition of the digital text as described in the title statement above. Here, “edition” is to be understood as “version”. The version number should be given in the @n attribute with the usual number system, i.e. ‘1.0’, ‘1.0.1’, ‘1.1’, etc. The date of the version should be given in the format year-month-day in the @when attribute, e.g. ‘2020-01-12’.

A complete edition statement may be as simple as this:

<editionStmt>

<edition n="2.0">Version 2.0 <date when="2020-01-06">6 January 2020</date> </edition>

</editionStmt>17.3.2.3 Extent

The <extent> element specifies the size of the file. The exact number of words should be given in the @n attribute as well as in plain text within the element, e.g.:

<extent n="339">339 words</extent>In a Menota XML file, each word will be contained in a <w> element, so the number of words can simply be regarded as equal to the number of <w> elements in the file. Words in the <supplied> element should preferably not be counted, since they have been added by the editor.

The main language of the diploma will be stated by the @xml:lang attribute of the <body> element of the file, using values like ‘nor’, ‘isl’, ‘swe’ and ‘dan’ for vernacular Nordic diplomas and ‘lat’ for diplomas in Latin. In the case of vernacular diplomas with some words, phrases or even sections in Latin, these parts should be encoded with the @xml:lang attribute for Latin. This way, an accurate number of words in each language can be stipulated. Cf. also ch. 17.4.2 below.

17.3.2.4 Publication statement

The <publisher> element specifies the body (publisher, archive) which has made the text available, e.g. the Medieval Nordic Text Archive (Menota).

The <availability> element specifies the accessibility of the text. We recommend adding a @status attribute with one of the three values: ‘free’, ‘restricted’ or ‘unknown’ (cf. the TEI P5 Guidelines, ch. 2.2.4).

Further specifications can be added in a <p> element. Almost all texts in the Menota archive are now available under an open CC license, and this should be stated in a <license> element with link to the Creative Commons website. Details on the transferral of this license should be added in a <p> element. A complete publication statement may thus look like this:

<publicationStmt>

<distributor>Medieval Nordic Text Archive</distributor>

<availability status="free">

<licence target="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/">

CC-BY-SA 4.0</licence>

<p>Licence accepted by the editor Nina Stensaker in a meeting

with Odd Einar Haugen, 07 Oct 2019.</p>

</availability>

</publicationStmt> 17.3.3 The file description: identification, contents, physical form and history of the source

The next part of the file description to be discussed here is the <sourceDesc>, which describes the source material (cf. the TEI P5 Guidelines, ch. 2.2.7).

We recommend that the <sourceDesc> opens with a statement on the availability of a photographic facsimile. This is stated by a <bibl> element with the @facs attribute. The value of this attribute is simply ‘yes’ if a facsimile is available. It may be briefly described in prose:

<bibl facs="yes">

Photos published with permission from the National Archives (digitalarkivet) in Oslo.

</bibl>Next in line, the <msDesc> element is the framing element into which the manuscript description is put. The description needs not consist of more than the basic information necessary to identify the source.

Within <msDesc> the following five elements are available, of which only the first is required:

| Elements & attributes | Explanation |

|---|---|

| <msIdentifier> | Groups information that uniquely identifies the diploma, i.e. its location, holding institution and shelfmark. |

| <msContents> | Contains an itemised list of the intellectual content of the diploma, either as a series of paragraphs or as a series of structured manuscript items. |

| <physDesc> | Groups information concerning all physical aspects of the diploma, its material, size, format, script, decoration, marginalia etc. |

| <history> | Provides information on the history of the diploma, its origin, provenance and acquisition by its holding institution. |

| <additional> | Groups other information about the diploma, in particular, administrative information relating to its availability, custodial history, surrogates etc. |

17.3.3.1 Diploma identifier

The only mandatory element within <msDesc> is <msIdentifier>, i.e. the diploma identifier. For <msIdentifier>, a number of sub-elements is available, among others, <country>, <region>, <settlement> (the TEI term for what most people will call city), <institution>, <repository>, <collection>, <msName> (name to be used in the archive, e.g. “1293 May 26 : Aga, Ullensvang”) and <idno> (an identifying number, here used for the number in Diplomatarium Norvegicum, e.g. DN 4:6.). For diplomas we recommend that at least the elements <idno>, <altIdentifier> and <msName> are included, since they provide the minimum amount of information necessary to identify a diploma.

The <idno> element contains the number in the Diplomatarium Norvegicum series, e.g. DN 4:6 for volume 4, diploma 6. Note that the <idno> element for diplomas differs from that of manuscripts, which are identified by their shelfmark (see ch. 14.3.1 above).

The <altIdentifier> is used for the volume and text number in the series Regesta Norvegica, as far as it goes (presently up to 1430). It is preceded by the abbreviation RN, e.g. RN 2:725 for the diploma which is referred to as DN 4:6.

The <msName> element contains any form of unstructured alternative name used for a manuscript, such as a nickname. For the diplomas we recommend that the <msName> element contains a uniform title, starting with the date and then the place, e.g. 1293 May 26 : Aga., Ullensvang. Occasionally a diploma can have several such names, in which case multiple <msName> elements are used, or perhaps rather several forms of the name, typically in a different language. The latter can be distinguished from each other by means of the @xml:lang attribute which is available on all TEI elements.

A <msIdentifier> for the Aga diploma may look like this:

<msIdentifier>

<idno>DN 4:6</idno>

<altIdentifier><idno>RN 2:725</idno></altIdentifier>

<msName>1293 May 26 : Aga, Ullensvang</msName>

</msIdentifier>17.3.3.2 Intellectual contents

A detailed description of a diploma’s intellectual contents is put in the <msContents> element, which is the next major sub-element of the <msDesc> element. The <msContents> element consists of one or more <msItem> elements.

The <msContents> element is wholly optional and is not required for a standard diploma header.

17.3.3.3 Codicological features

The next major element in the <msDesc> element is a physical description, <physDesc>. This is an element with several sub-elements, all of which are optional. We only recommend a single element here, the <sealDesc>, which states whether there is a seal or not, e.g.

<physDesc>

<sealDesc>

<seal>

<p>No seals</p>

</seal>

</sealDesc>

</physDesc>or, if applicable, more detailed:

<sealDesc>

<seal>

<p>Four seals missing, only the strips left.</p>

</seal>

</sealDesc> 17.3.3.4 The history of the diploma

The <history> element contains information on the history of the diploma. We recommend that the <origin> element always is included, containing two further sub-elements, <origPlace> and <origDate>:

<history>

<origin>

<origPlace>Aga, Ullensvang, Vestland fylke</origPlace>

<origDate>1293-05-26</date>

</origin>

</history> The <origPlace> element should specify the place of composition, as far as it can be ascertained. For Norwegian diplomas, we recommend the locale (e.g. farm, smaller area, village), the modern-day municipality (kommune) and the modern-day county (fylke). Since some of the new counties have ambiguous names, we suggest adding ‘fylke’, e.g. ‘Vestland fylke’ (as opposed to the region ‘Vestlandet’). Note that as of 1 January 2024, there will be 15 counties in Norway, down from 19 until 2018 (or even as few as 11 for the period 2018–2023). Also note that the number and names of municipalities (kommuner) changed considerably as of 1 January 1964, and that some changes are still under way. In the example above, the place of composition is Aga [farm], Ullensvang [municipality], Vestland fylke [county].

In some cases, the place of composition is unknown. We suggest using “No place” in square brackets, [No place]:

<history>

<origin>

<origPlace>[No place]</origPlace>

</origin>

</history> Optionally, we suggest that the exact location should be given by way of the geolocation in Kartverket.

The <origDate> can in many diplomas be stated by day, month and year, but there are also many diplomas with less specific or less certain dating. Based on the attribute class att.datable.w3c we suggest the following table for stating the date of a document:

<date when="1225">The year 1225</date>

<date when="1225-03">March 1225</date>

<date when="1225-03-12">12 March 1225</date>

<date when="--03-12">12 March</date>

<date when="--03">March</date>

<date when="---12">Twelfth of the month</date> As can be seen in this table, there are strict rules for the value of the @when attribute, but there are fewer restrictions for the contents of the <date> element. For example, the value ‘1225-03-12’ can be an encoding of e.g. “12 March 1225”, “12.3.1225”, “12.03.1225”, “March 12, 1225” or “the third of March 1225”, to name just a few.

Furthermore, it should be noted that dates (as well as locations) sometimes are uncertain. If a likely candidate can be established, we recommend using square brackets, e.g. [1301 May 17] (and similarly for the location, e.g. [Stavanger]. A higher degree of uncertainty can be indicated by a question mark. This is the convention of Diplomatarium Norvegicum as well as of Regesta Norvegica.

Note that while the date of a diploma can be quite specific, often down to the day, month and year, in other cases it can only be dated by a year or an even longer period of time. We recommend these attributes for less specific dates: @notBefore and @notAfter to circle in a possible date.

The oldest preserved Norwegian diploma, DN 1:3, can not be dated more precisesly than around July in the period 1207–1217, so the <origDate> element might look like this:

<history>

<origin>

<origDate notBefore="1207-07" notAfter="1217-07">[1207–1217 around July]</origPlace>

</origin>

</history> 17.3.4 The encoding description

The <encodingDesc> documents the relationship between the digital edition and the source it is based upon. It is an optional part of the header, but we recommend that it contains information on the standard of encoding and level of quality. It should have two sub-elements: a <projectDesc> and an <editorialDecl>.

The <projectDesc> can state the standard of the encoding in prose, e.g. “This text has been encoded according to the standard set out in The Menota Handbook, version 3.0, at https://menota.org/handbook.xml”.

The <editorialDecl> uses the <correction> element with the @status attribute to specify the level of quality control. Attribute values (according to TEI) are ‘high’, ‘medium’, ‘low’ and ‘unknown’. The TEI P5 Guidelines, ch. 2.3.3 offer these definitions for the possible values:

- high: the text has been thoroughly checked and proofread

- medium: the text has been checked at least once

- low: the text has not been checked

- unknown: the correction status of the text is unknown

Once the @status attribute is given a value, the <correction> element may be empty. However, if desired, further specification can be given in prose within a <p> element.

Next within the <editorialDecl> element, a <normalization> element with a Menota-specific @me:level attribute is used to specify the level on which the text is encoded. The focal levels are ‘facs’, ‘dipl’ and ‘norm’, but other levels can also be used in the transcription, e.g. a ‘pal’ level for a very close paleographical transcription. Also here, a description in prose may be added in a <p> element. Note that more than one level may be specified, simply separating the values by whitespace:

<editorialDecl>

<normalization me:level="facs dipl norm">

<p>This text has been encoded on three levels: facsimile, diplomatic and normalised.</p>

</normalization>

</editorialDecl>

Finally within the <editorialDecl> element, an <interpretation> element is used to specify the amount of lexical and grammatical annotation in the encoded text. We suggest two attributes, @me:lemmatized and @me:morphAnalyzed, both with the values: ‘completely’, ‘partly’ and ‘none’. An additional description in prose may be added in a <p> element. A lemmatised text will have lemmata (i.e. dictionary entries) added in the @lemma attribute of the <w> element and usually also the word class (part of specch) in the @me:msa attribute, while a morphologically annotated text will have grammatical forms specified in the @me:msa attribute of the same element. See ch. 5.3 above for a general overview and ch. 11 above for details on this lexical and morphological encoding.

A complete <encodingDesc> may look like this:

<encodingDesc>

<projectDesc>

<p>This encoding follows the standard set out in <title>The Menota Handbook</title>

(version 3.0), at <ref target="http://www.menota.org/handbook">

http://www.menota.org/handbook</ref> as of <date>2019-12-12</date>.</p>

</projectDesc>

<editorialDecl>

<correction status="high">

<p>This text has been transcribed directly from photographic colour

facsimiles of the diploma.</p>

</correction>

<normalization me:level="facs dipl norm">

<p>This text has been encoded on all three focal levels: facsimile,

diplomatic and normalised.</p>

</normalization>

<interpretation me:lemmatized="completely" me:morphAnalyzed="completely">

<p>The whole text has been lemmatised and morphologically annotated.</p>

</interpretation>

</editorialDecl>

</encodingDesc> 17.3.5 The profile description

The <profileDesc> is an optional part of the header, but we strongly recommend that the language(s) used in the source are listed here within the element <langUsage>. This element contains one or more <language> elements with an @ident attribute each. The value of @ident should be a three-letter code, based on the international standard ISO 639-2.

A <profileDesc> may look like this:

<profileDesc>

<langUsage>

<language ident="nor">Norwegian</language>

<language ident="lat">Latin</language>

</langUsage>

</profileDesc>The languages defined here will be used in the actual encoding of the text. If, for example, a diploma is wholly in Norwegian, this should be specified as an attribute to the <body> element. See ch. 17.4.2 below.

Note that we do not recommend stating language periods, such as “Old Norwegian”, “Middle Norwegian”, “Early Modern Norwegian” or the like. The date in the <origDate> element (ch. 17.3.3.4 above) will give a good indication of the period, and the encoder need not worry about distinguishing between periods.

17.3.6 The revision description

Even if this is an optional part of the header, it is essential that all changes to the file are recorded, apart from, perhaps, very minor changes. Each change is described i a separate <change> element. Within it, the <date> is given first, then the <name> of the reviser (preferably with affiliation), and, finally, a description in prose of the actual change.

A short series of <change> elements may look like this:

<revisionDesc>

<change> <date>2020-01-10</date> <name> <persName>Odd Einar Haugen</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName> </name>:

Minor changes to the transcription and additions to the header.

</change>

<change> <date>2020-01-07</date> <name> <persName>Nina Stensaker</persName>

<orgName type="affiliation">University of Bergen</orgName> </name>:

Minor changes to the transcription after a proofreading.

</change>

</revisionDesc>17.4 Text

While the encoding of codices and fragments of codices usually will have a single <body> element within the overarching <text> element, we suggest that the particular needs of diploma encoding can be served by adding a <front> and a <back> element, as shown in ch. 3.2 above:

| Elements | Contents |

|---|---|

| <TEI> | The TEI document begins here, |

| <teiHeader> . . . </teiHeader> | the header goes here, |

| <text> | the text itself begins here, |

| <front> . . . </front> | any front matter goes here, |

| <body> . . . </body> | the main body of the text goes here, |

| <back> . . . </back> | any back matter goes here, |

| </text> | the text ends here, |

| </TEI> | the TEI document ends here. |

17.4.1 Front

We recommend that the front matter contains a uniform title of the diploma (place, date, edition), optionally background information, and finally abstracts from Diplomatarium Norvegicum and, if published, from other sources such as Regesta Norvegica and Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi

The contents of the <front> element can be organised as follows:

| Elements & attributes | Explanation |

|---|---|

| <div> | Contains all front matters. |

| @type | Indicates what type of section it is. |

| ‘abstracts’ | Contains background on the diploma, if appropriate, and one or more abstracts of its contents. Opens with a <head> element specifying (a) Place, (b) Date and (c) Edition of the diploma. |

Within the <div> specified above, there are several subordinate <div> elements with appropriate attributes and values:

| Elements & attributes | Explanation |

|---|---|

| <div> | Contains a separate, subordinate section of the <front> element. |

| @intro | Information about the background of the diploma. |

| @source | Indicates which source the division contains. |

| ‘DN’ | An abstract from Diplomatarium Norvegicum. |

| ‘RN’ | An abstract from Regesta Norvegica (if published). |

| ‘CCN’ | An abstract from Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi (if published). |

| ‘editor’ | Optionally, an abstract written by the editor of the transcription. |

The text of the abstracts may be inserted in full here, or it may be given by a link to an external online source.

17.4.2 Body

This is the actual text of the source. In most cases, the text will be rendered only on the diplomatic level, so there is no need for the <choice> element and the corresponding <me:facs>, <me:dipl> and <me:norm> levels. The header should specify the level of text representation, however (cf. ch. 17.3.4 above).

This means that a diploma may have a rather simple encoding, much like the one exemplified in app I.

Although not strictly required, encoding words in the <w> element is encouraged, as it makes it possible to annotate the text for morphology. Similarly, using the <name> element for all personal names and place names adds value to the transcription, both by itself and as part of a corpus where it can be used to find similar references. See ch. 12 for details of the encoding of names.

Since the diplomas are written in several languages, particularly Norwegian and Latin, we strongly recommend that the language is specified. This can be done as an attribute to the <body> element, like this example of a diploma written in Norwegian:

<body xml:lang="nor">If the diploma contains text in another language, e.g. Latin, these words (or divisions) can be singled out by the same type of attribute:

<w xml:lang="lat">Anno</w>

<w xml:lang="lat">Domini</w>For longer passages, elements such as <div> (chapter), <p> (paragraph), <s> (sentence) and <quote> (quote) can be used, spanning more than a single <w> element.

Note that the language codes used here must be defined in the <profileDesc> of the header, cf. ch. 17.3.5 above.

17.4.3 Back

The back matter may contain images of the diploma, other transcriptions and translations.

They may be given within <div> elements with appropriate attributes and values.

| Elements & attributes | Explanation |

|---|---|

| <div> | Contains a separate section of the back matter. |

| @type | Indicates what type of section it is. |

| ‘image’ | Photographic facsimile of the diploma. |

| ‘transcription’ | Pencil transcription made by scholars working at Gammelnorsk ordboksverk. |

| ‘translation’ | Translation of the diploma. |

Translations of Norwegian diplomas were made by Finn Hødnebø 1960 for all diplomas up to 1300, and by Erik Simensen 2002 for the subsequent diplomas up to and including 1310 (both as part of Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi). Sporadic translations are found in collections for certain areas, such as the one by Eyvind Fjeld Halvorsen and Magnus Rindal 2009 for Ringerike.

17.5 Example files

We offer two diploma files for download:

- The Aga diploma (1293-05-26) as a sample XML file NB! Not updated for v. 4.1 beta.

- The Bergen diploma (1309-02-06) as a sample XML file NB! Not updated for v. 4.1 beta.

Please note that some browsers may try and interpret and open these sample files. In order to download the file to your disk, use alt-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows) on your browser, unless your browser has other preferences.

Almost all texts in the Menota archive can be downloaded as XML files. This means that files in the archive can be inspected, and, if convenient, used as a template.

17.6 Bibliographical references

This is a list of bibliographical references in the chapter. At a later stage, it will be moved to the shared bibliography of the handbook.

Agerholt, Johan. 1929–1932. Gamalnorsk brevskipnad. Etterrøkjingar og utgreidingar i norsk diplomatikk. Vol. 1, Formelverk i kongebrev på norsk 1280–1387. Vol. 2, Eldre formelverk. Oslo: Gundersen.

Berulfsen, Bjarne. 1948. Kulturtradisjon fra en storhetstid. Oslo: Gyldendal.

CCN = Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi. See Hødnebø (1960) and Simensen (2002).

DN = Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Vol. 1‒20, 1847‒1915; vol. 21, 1976; vol. 22, 1990‒1992; vol. 23, 2011. Christiania/Kristiania/Oslo: Kjeldeskriftfondet.

Hagland, Jan Ragnar. 1976. “Avskrift ‘orð ifra orðe’. Gransking av ein kontrollert avskrivingsprosess frå mellomalderen”. Maal og Minne 1976: 1–23.

Halvorsen, Eyvind Fjeld, and Magnus Rindal, eds. 2009. Middelalderbrev fra Ringerike 1263–1570. Published by Bjørn Geirr Harsson for Ringerike Slektshistorielag. [Hønefoss]: Kolltopp forlag.

Hamre, Lars. 1972. Innføring i diplomatikk. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. 60 pp.

Haugen, Odd Einar. 2018. “Høgmellomalderen (1050–1350).” In: Tidslinjer, ed. Agnete Nesse, 197–292. Vol. 4 of Norsk språkhistorie, eds. Helge Sandøy and Agnete Nesse. Oslo: Novus.

Hødnebø, Finn, ed. 1960. Norske diplomer til og med år 1300. Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi, Folio Serie, vol. 2. Oslo: Selskapet til utgivelse av gamle norske håndskrifter.

Jørgensen, Jon Gunnar. 2013. “Diplomer, lover og jordebøker”. Ch. 5 in Handbok i norrøn filologi, edited by Odd Einar Haugen, 250–301. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Jørgensen, Jon Gunnar. 2020. “Urkunden, Gesetze, Landbücher”. Ch. 3 in Handbuch der norrönen Philologie, vol. 1, edited by Odd Einar Haugen, 155–216. Oslo: Novus. OA: http://omp.novus.no/index.php/novus/catalog/book/14

KLNM = Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder. 22 vols. 1956–1978. Oslo/Stockholm/København.

Simensen, Erik, ed. 2002. Norske diplom 1301–1310. Corpus Codicum Norvegicorum Medii Aevi, Quarto Series, vol. 10. Oslo: Selskapet til utgivelse av gamle norske håndskrifter.

RN = Regesta Norvegica. Vol. 1–. Kristiania: Det Norske Historiske Kildeskriftfond, Oslo: Kjeldeskriftfondet, 1898, 1978–.